In the 12th century, the langue d'Oc was spoken south of the Loire. The Roman Church, which spoke Latin and was based in Rome, was perceived as foreign. Not to mention the fact that Pope Innocent III forbade the Provençal people from having a Bible written in their own language, Occitan; to be more precise, he forbade any translation of the Bible into dialect. And the people of Languedoc felt that the dogmas of the Church were detached from the word of Christ.

In Carcassonne, the Cathars are everywhere... and nowhere. They were everywhere you went, and their presence permeates the place forever. Today, Carcassonne is inhabited by faith. There are no fewer than 13 Catholic churches** and some 9 chapels**, for a population of 47,000 inhabitants**, as well as an Orthodox parish (Saint-Gaudéric, housed in the église Saint-Saturnin de Maquens) and 5 Protestant churches. Not forgetting, of course, the cathedral of Saint-Michel.

This fabric of places of worship, built up over time in the Catholic faith, was also built on protest movements deemed impious, culminating in the "Albigensian Crusade", which began in 1209. Then came the Inquisition.

A turning point was reached after this dark period of repression, which lasted 120 years. Places of worship considered heretical, although dedicated to Christ, were destroyed or transformed, and new churches were erected, such as Saint-Vincent, built from 1269 on the orders of Saint-Louis, King Louis IX.

It was also during this period of reappropriation of the Languedoc region, and Carcassonne in particular, by the Roman Church and the King, that it was decided to build a new town on the outskirts of the citadel, the Ville Basse, or Bastide Saint-Louis**, which came into being in 1247.

Who were the Cathars?

It was on this soil that Paulicianism, a Christian religion of Armenian origin, arrived in Lombardy after a spell in Bulgaria, and eventually spread to Languedoc. The people of Languedoc allowed themselves to be imbued with this faith, which gave pride of place to the teachings of Christ - who alone was important to them - and which rejected many ecclesiastical dogmas. They saw themselves as "good men" and "good women".

Their disagreements with the Church were profound. The Cathars believe that God is absent from this world (otherwise, evil would not exist), respect animals (they are willing vegetarians), believe in reincarnation, reject war, refute Hell and contest the sacraments of the Roman Church. That's quite a lot.

But that's not all: they see no need for places of worship, since the Holy Spirit is everywhere and the word of Christ can be spoken anywhere. They disapprove of private property, even though the Church is the largest landowner on the planet. They practise asceticism while the Vatican lives in opulence. In short, they believe that the Church is betraying the thought of Christ. There are better ways of taking communion.

Saint-Félix-de-Caraman nommée aujourd’hui Saint-Félix-Lauragais, où se tint la 1ère assemblée historique des Cathares.

- © olivier.laurent.photos / ShutterstockFor their part, the local lords pacted with the Albigensians and the castles in the Carcassonne region all rallied to the Cathar cause. The Church, which had known it was under threat ever since a Cathar assembly had met at Saint-Félix-de-Caraman in 1176 to organise its cult, had no intention of giving in. It declared any Languedocian who opposed its dogmas to be a "heretic". The Cathars had just been characterised and designated as its enemies.

Flight comparator for Carcassonne

Find your Flight to CarcassonneThe witch-hunt: the Albigensian Crusade

In 1209, the king's army of 6,000 soldiers and looters drove the villagers out of Carcassonne. Thus began the crusade against the Cathars, known as the Albigensian Crusade, which lasted 20 years and was the sinister prelude to the Inquisition. The following year, the 600 Cathars who refused to recant were burned.

Harsh confrontations under the Inquisition

- © Gorodenkoff / ShutterstockIn 1229, the Inquisition took over and lasted for a century, forever changing the face of the countryside through spectacular depopulation and the fall of Cathar castles that never recovered: the four fortresses of Lastours in Cabaret, near Carcassonne, Queribus, Saissac, Lapradelle Puilaurens, Termes, Villerouge-Termenès and Puivert.

Château Aquilar, a royal citadel, was, along with the castles of Peyrepertuse, Puilaurens, Quéribus and Termes, nicknamed "The Five Sons of Carcassonne".

- © BAO-Images Bildagentur / ShutterstockThe Consuls of Carcassonne alerted the Pope to the desertification of entire regions of Occitania, with the Inquisition driving people out of the country altogether. From the fall of Montségur in 1244 until the end of the 13th century, many people moved to Corsica and Spain, but also to Italy, Sicily and particularly Lombardy, where Paulicianism was still active.

The Cathar castle of Villerouge-Termenes.

- © LianeM / 123RFThe last Cathars were reputedly massacred in 1321 at the Château de Villerouge-Termenès. 800 years after their disappearance, the Cathars are still present in Carcassonne, in the manner of a legend, despite having been defeated by the double repression of the Crusades and the Inquisition, by the Kingdom of France and the Clergy.

The impact for Carcassonne

At the end of the Albigensian Crusade, the king regained power and established a seneschalcy in Carcassonne to defend order and his interests. Between 1226 and 1245, the seneschal, the mayor of the time, transformed the medieval city into a fortified citadel to prevent any future invasion or seizure of power from outside.

Carcassonne was architecturally transformed by the Albigensian Crusade.

- © JaySi / ShutterstockA second wall, flanked by round towers (Gallo-Roman towers were horseshoe-shaped), often low and without roofs, was erected. In the 19th century, Viollet-le-Duc was responsible for creating the slate roofs we see today.

The Basilica of Saint-Nazaire and Saint-Celse

The Basilica of Saint-Nazaire-et-Saint-Celse

- © milosk50 / ShutterstockThe church of Saint-Nazaire, built in the 11th century to the south of the citadel in pure Romanesque style, was home to the Cathars and their cult. Listed as a Historic Monument, it was remodelled in the 19th century by Viollet-Le-Duc, thanks to whom it became a basilica in 1898.

Although it is not original, its stained glass windows, centred on the life of Christ, bear witness to the historical split between the Cathar cult, which emphasised the doctrine of Jesus, and the Catholicism of the time, which was all about political power. It is an ancient cathedral.

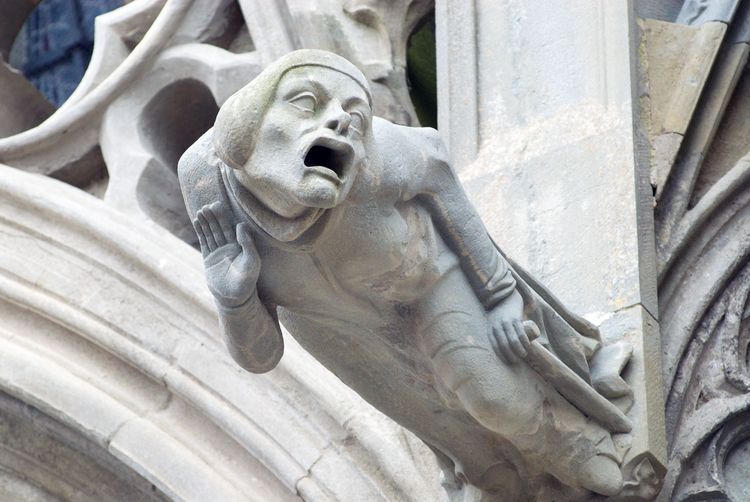

The witch-hunt left its mark on the town. Here, a gargoyle on the front of Saint-Nazaire church.

- © Dmitry Chulov / ShutterstockIts 17th-century organ has been listed as a historic monument since 1970. The basilica itself was listed as a Historic Monument in 1840.

Saint-Vincent Church

Saint-Vincent church in the heart of Carcassonne

- © Sergey Novikov / ShutterstockThe church of Saint-Vincent, built in the bastide of Saint-Louis rather than in the walled city, was destroyed during the Inquisition. At the request of Saint-Louis, it was rebuilt on the same site in pure Languedoc Gothic style. It boasts a generous nave measuring 20.25 metres, which took 60 years to build, and a full vault 23.5 metres above the ground, as well as 15th-century rose windows and stained glass windows.

To ensure that it can be heard far and wide, it is equipped with a carillon of 47 bells suspended from the campanile of the tower, which is over 50 metres high. Access is via a 232-step staircase that closes 1 hour before the church closes, for a fee of €2.50. It's one of the best views Carcassonne has to offer.

If you have more earthy feet, you might prefer to admire the paintings by Jacques Gamelin (his 'Saint-Roch'), Nicolas Mignard and Pierre Subleyras on the ground floor, which can also be found in the Carcassonne Fine Arts Museum.